Hi there! I share a weekly update on ways to be a better marketer, brand-maker, team-builder, and person. If you enjoy this, you can share some love by hitting the Substack heart button above or below.

I’m one month into my business book reading challenge, and wow, did it start off with a bang. I just finished Unlocking the Customer Value Chain, which you can maybe guess by the subject line of this email, is all about disruption. I’ll share all my notes and highlights below.

I give the book two thumbs up 👍👍

Have you read anything good lately? Drop me a reply or leave a comment. I’d love to hear from you.

Hope you have a great week,

Kevan

The formula for disruption

Unlocking the Customer Value Chain by Thales Teixeira

Summary:

An insightful look at modern-day disruption. The book covers all the ways to guard against being disrupted, as well as strategies for finding opportunities to disrupt existing markets. In short:

Businesses serve customers.

Customers follow a discrete set of steps in order to choose, purchase, and use a product or service.

Business model disruption happens because of decoupling: stealing customers by “decoupling” specific activities that customers normally perform in the course of shopping.

Disruption does not happen because of technological innovation.

Disruption happens because new businesses find ways to deliver value to customers in new ways.

You can check out the book here on Amazon, and all my highlights are below.

Individual instances of disruption aren’t nearly as unique as most executives assume.

—

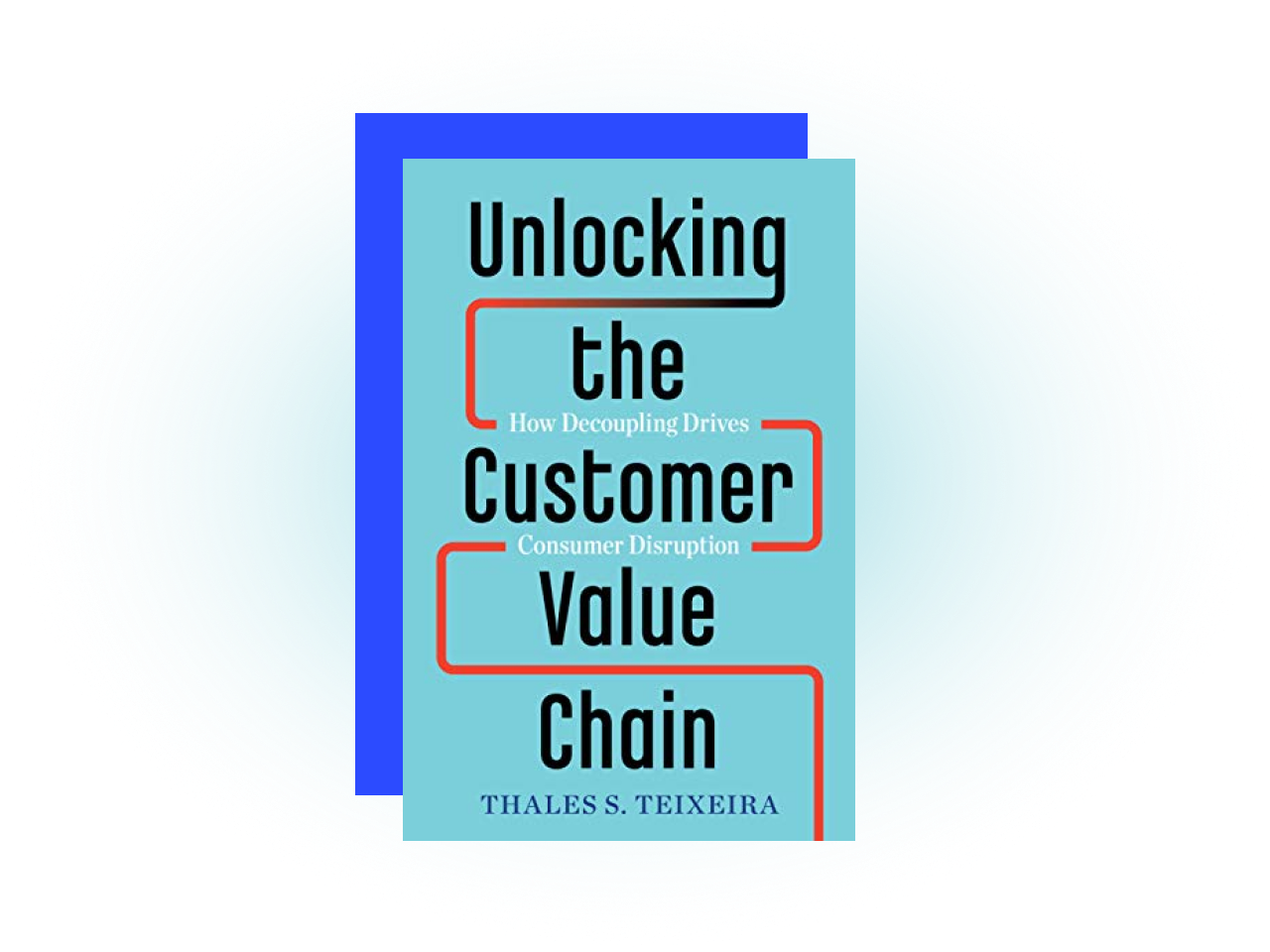

About the customer value chain, or CVC.

A CVC is composed of the discrete steps a typical customer follows in order to select, buy, and consume a product or service.

CVCs vary according to the specifics of a business, industry, or product.

For example, the key stages in a CVC for purchasing a flat-screen TV involve going to a retailer, evaluating the options available, choosing one, purchasing it, and then using the TV at home. For a beauty product such as skin cream or for a videogame, the value chain is basically the same. In the case of videogames, players evaluate the available game titles, choose one or more, purchase it, and then play it.

—

disrupting Best Buy:

To facilitate comparison shopping, Amazon created a mobile application (app) that allowed shoppers in brick-and-mortar stores to search, scan the barcode, or snap a picture of any product to easily discover Amazon’s price. This enabled Amazon’s customers to easily break the connection between choosing a product and purchasing it. Best Buy did the former, Amazon the latter.

—

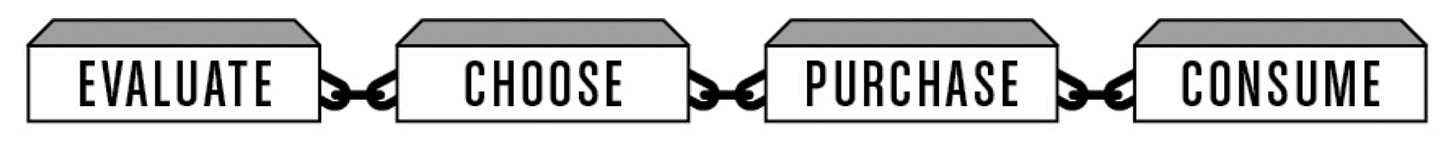

Disruptors were decoupling discrete activities that customers performed.

—

Examples of decoupled activities and their disruptors

Source: Adapted from Thales S. Teixeira and Peter Jamieson, “The Decoupling Effect of Digital Disruptors,” European Business Review, July–August 2016, 17–24.

—

I wanted to advise these companies to deemphasize other concepts that people were using in relation to disruption (for instance, the “sharing economy,” “webrooming,” and “freemium”) and to see everything in terms of just one phenomenon: decoupling.

—

on software disruption:

Home PC users do not need to pay the $149.99 up-front cost to use the product. Instead, they might pay just $6.99 per month. We can regard SaaS as a special case of decoupling usage from ownership.

Freemium models used by Dropbox, an online storage service, go even further, decoupling usage from (pre)payment. Users of a basic software or service online do not need to pay anything up front.

—

Our natural tendency is to think that the problems we face are unique to us.

In our highly specialized professional worlds, we tend to think in terms of silos—particular fields, disciplines, functions, or specialties. Such extreme focus has its benefits, but it can also prevent us from spotting general patterns that can help us develop more appropriate responses.

—

Ryanair’s extraordinary success alerts us to an important and counterintuitive truth about consumer markets. Many businesspeople assume that innovative products and services and the advanced technology behind them determine market share outcomes. If you want to disrupt a market in the digital age, they think, get your hands on the latest technology that nobody else has and use it to develop innovative offerings. On the strength of these beliefs, companies invest billions in research and development to secure patents for proprietary technologies. And yet technologies may not be the grand solution that executives in the digital age often suppose.

Ryanair’s planes and booking systems were comparable to those of other airlines, and its product, the customer experience, was arguably much worse. So how could Ryanair win in a highly competitive market with an inferior product? The company possessed something else that competitors lacked: an innovative business model.

—

Upstarts typically catch incumbents by surprise; the latter don’t see business model innovation as part of a pattern. But if you can spot a wave of digital business model innovation early enough, you can get ahead of it. You can anticipate how likely startups will be to join the wave, and you can craft an appropriate response in advance.

“Wave-spotting” is an essential skill for executives seeking to understand and master digital disruption in their industry.

—

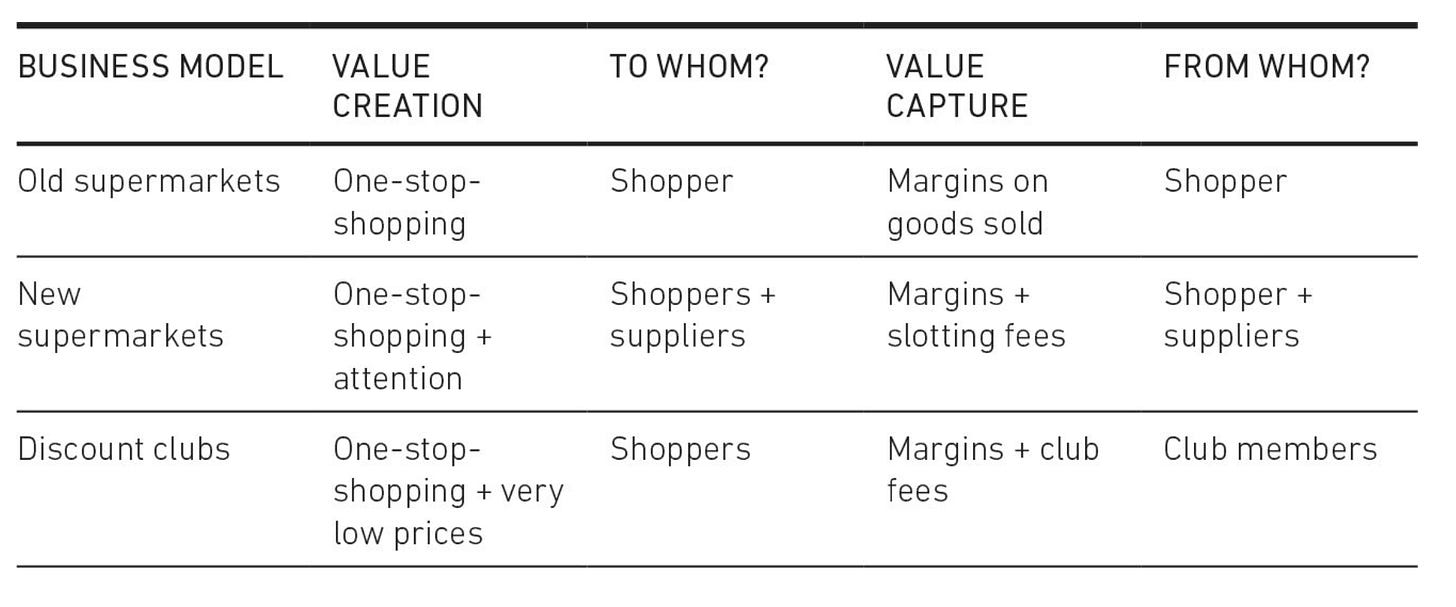

For our purposes, here’s a simple definition, one that applies both to large businesses with established models and to small startups that are experimenting with and evolving their models: A business model specifies how the firm creates value (and for whom), and how it captures value (and from whom).

—

A business model, as defined above, describes how a business is supposed to function in theory. Although businesses will differ from one another in their particulars (name, location, number of employees, financials, and so on), a model allows us to look beyond the particulars to identify conceptual similarities and differences between businesses, whether or not they happen to operate in the same industry.

—

As of this writing, slotting fees were the top source of income for the average national U.S. supermarket chain, Walmart excluded. Margins on goods sold constituted only the fourth-largest income source.

—

Guess what percentage of Costco’s total 2016 profits of $2.35 billion owed to the fees it charged its members.

Fifty percent?

Eighty percent?

One hundred percent?

Try 112 percent. Costco lost money in its traditional supermarket retail business model and more than made up for it with membership fees.

—

Grocery stores: Business models

—

The appearance of business model innovation in and across industries happens so suddenly that executives and entrepreneurs often struggle to understand it.

Disruptors tend to use a surfing metaphor, perceiving promising business models as powerful ocean waves. Seeking to catch and ride these waves, they anticipate them by directing their gazes in a direction where waves will likely appear. When they sense that a wave is imminent, they position themselves by paddling directly in front of the wave.

Of course, spotting the right wave to ride requires focus and some luck, and staying atop of the wave once it appears requires learning and patience.

For incumbents, the spread of business model innovations feels far less fun, and far more threatening. Incumbents tend to think of them, consciously or not, as wildfires that pop up unpredictably, propagate quickly, and wreak devastation in their paths. Their instinctive response is to suppress the wildfire by attacking or buying the startup.

—

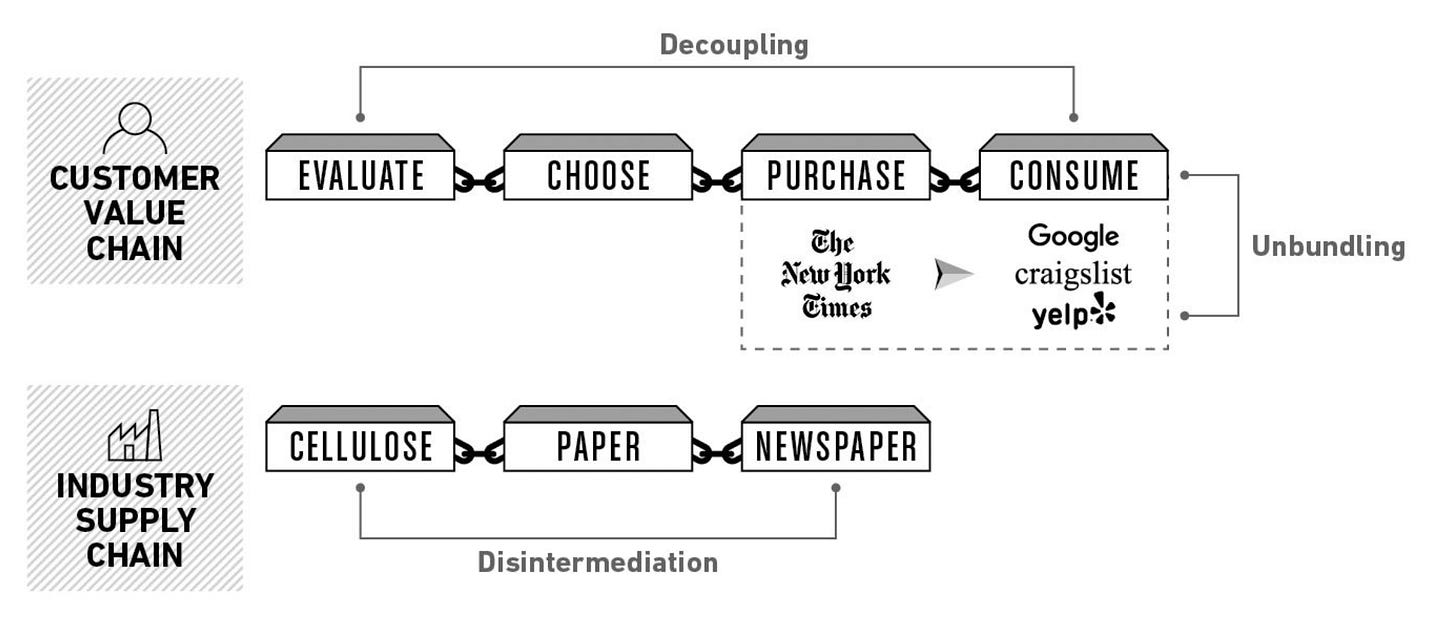

The Internet’s three great waves of business model innovation

To date, the internet has seen three great waves.

Unbundling

Disintermediation

Decoupling

Unbundling

Physical newspapers such as the New York Times used to be a bundle of content, including news articles, classified advertisements, and restaurant reviews. The internet enabled businesses such as Google, Craigslist, and Yelp to specialize in each of these types of content, respectively, thereby unbundling the newspaper.

Content that could be unbundled profitably had been. This first wave of business model innovation began to give way to a new wave: the disintermediation of goods and services.

Disintermediation

Prior to the internet, for instance, many consumers used travel agents to book vacation airfare, accommodations, and activities. These businesses didn’t produce the services they sold. They only act as intermediaries.

The financial services industry saw similar disintermediation, for example in the appearance of websites allowing investors to purchase and sell stocks without a broker or advisor. Unlike unbundling, disintermediation affected both digital and physical service providers. Therefore, its impact was arguably larger, as it afflicted many more industries, from home video (disrupted by Netflix) and home improvement (disrupted by BuildDirect) to dating services (disrupted by eHarmony).

Decoupling

Stealing customers by “decoupling” specific activities that customers normally performed in the course of shopping.

The first wave, unbundling, largely took place at the product level and in the consumption stage: some consumers read only newspaper articles, others only the classified ads. The second wave, disintermediation, occurred within the supply chain (e.g., cellulose companies selling pulp directly to the newspapers, bypassing paper manufacturers). Decoupling also broke down important linkages, but this time between customer activities, not products or supply chain stages

—

How decoupling differs from unbundling and disintermediation

—

As Jim Collins put it more than a decade and a half ago in his bestselling book Good to Great,

“Technology is an accelerator, never a creator of momentum and growth.”

—

Forget for a moment about wearables, drones, chat bots, the internet of things, machine learning, and augmented or virtual reality. They all might have a place in your future business, but your role, as a senior business executive, is to figure out the business side.

Stop blaming your lemonade! The truth is that the upstart’s lemonade tastes the same as yours, or maybe even worse. It’s the new business model that is stealing your customers, not the product.

—

If you’re still keen on constantly identifying new technology innovations for your company, then it’s time to make a change.

You should spend as much time or more evaluating and evolving your firm’s business model(s) as you do worrying about new technologies.

—

example of decoupling:

From the customer’s perspective, Airbnb broke apart the act of using real estate from owning it.

—

Focusing on competitors has worked well in the past, and it might still work in some situations, but it has become less applicable for companies competing in markets threatened with disruption.

—

Types of decoupling

Value creating, value capturing, and value eroding

Whether an offering is a physical product or a service, consumable or durable, all of these activities can be classified as either value creating, value capturing, or value eroding.

Value-creation decoupling includes businesses that break the links between two or more value-creating activities. The decoupler offers one of these value-creating activities, while the incumbent that has been decoupled retains another value-creating activity.

Example:

Twitch took videogame spectatorship for itself, but it does not develop videogames to be played. It left that activity for incumbents like Electronic Arts.

In value-eroding decoupling, disruptors break the links between value-eroding and value-creating activities.

Example:

In videogames, Steam allows customers to stream videogames over the internet, just as Netflix does for movies and TV shows. With Steam, players no longer have to get off the couch and go to a physical retailer (a value-eroding activity) in order to play a game (a value-creating one).

The third type of disruption, value-charging decoupling, includes businesses that decouple value-creating and value-charging activities.

Example:

Mobile game developer SuperCell allowed consumers to play most of its games for free, charging value by selling digital goods (in-app purchases) to the company’s most loyal players. In effect, SuperCell broke the link between buying a game (value charging) and playing it (value creating).

—

Map the stages of your customer’s CVC to discover where you create value, where you charge for it, and where you sometimes erode it.

Then ask yourself three questions:

Can you deliver more value in the value-creating activities without charging more?

Can you afford to capture less in the value-charging activities, everything else being equal?

Can you reduce eroded customer value without diminishing what you’re offering or capturing?

—

Examples of changing customer behavior

—

—

The customer of Kiehl’s, decoupling Sephora, is actually your customer, too. She buys cars, entertainment, financial services, and so on. And while she can choose from different options in each case, she does not have a different thought process for choosing. She does not have a perfume-buying brain, or a separate car-buying brain.

—

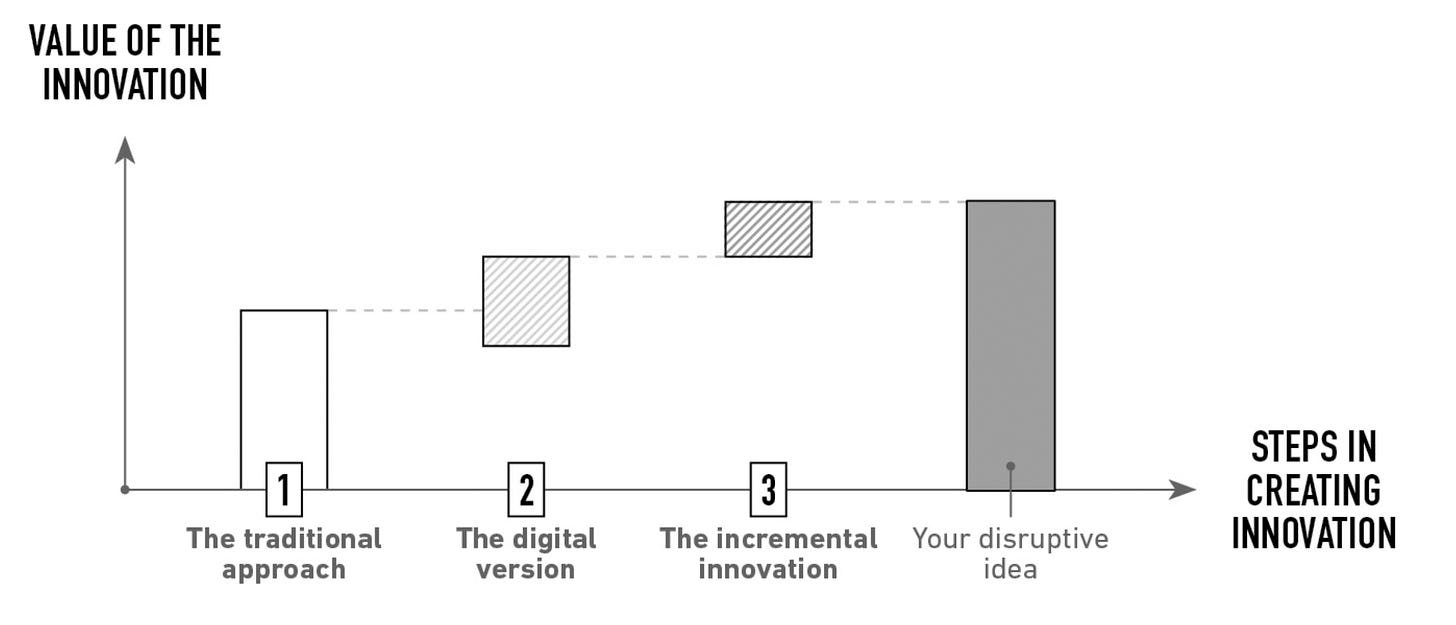

How to de-risk yourself from disruption

You can deliberately engineer business model innovation and decoupling. In other words, there is a “recipe” that will help keep risk to a minimum.

I typically recommend that entrepreneurs or executives embrace the customer’s vantage point and organize their thinking in terms of three layers.

❶ The first layer is to articulate the current or standard business model.

After all, most startups need to pull customers away from existing businesses or activities (e.g., dry cleaning versus do-it-yourself clothes washing). Customers evaluate the startup in comparison to what they already have. If you want to thoroughly understand a new business idea, you must take the current reality as your foundation.

❷ The second layer is to develop the digital equivalent of the standard model.

Almost all young entrepreneurs I meet today incorporate the internet into their business ideas. When comparing their innovative products to the best options that are currently available, the less elaborate ideas tend to focus on simply translating or “porting” a traditional business model onto the internet. As an example, homeowners traditionally hire housekeepers, gardeners, and others to help with common household chores. TaskRabbit, the digital equivalent, lets you hire people, but do so over the web. Likewise, the startup company Washio created a mobile app that allowed you to request digitally that your dry cleaning be picked up and delivered, saving you the trouble of going to the dry cleaner’s yourself.

❸ With this digital equivalent layered on top of the standard business model, the third and final layer for entrepreneurs and executives is to determine how to innovate on top of digital business models.

Some entrepreneurs I’ve met understand that the mere porting of a business model online isn’t enough. It might benefit users, but it creates downsides, too. TaskRabbit accelerates the process of choosing people to perform chores for you, but it’s also riskier, since it requires that you allow complete strangers inside your home. Washio offered convenience, but at a price.

—

Considering the benefits and costs, smart entrepreneurs try to layer on top of their digital business idea an innovation that transcends mere digitization, and that produces a functional benefit for customers.

—

Founders of Hello Alfred innovated upon the TaskRabbit model by outsourcing the management of TaskRabbit workers to personally assigned butlers, or “Alfreds.” For users, the presence of a butler on the scene allowed for a more trustworthy and reliable service.

—

Designing innovative business models

—

How to be a successful decoupler

Successful decouplers perform five key steps, either deliberately or instinctively, that unsuccessful ones don’t.

Step 1: Identify a Target Segment and Its CVC

It’s so important to get this first step correct. In fact, I often spend 50 percent or more of my time working with companies on this single step. The CVC is the blueprint of digital disruption, and it must be fleshed out so that it is both accurate and comprehensive. Otherwise, your attempt at decoupling likely won’t succeed.

Step 2: Classify the CVC Activities

Step 3: Identify Weak Links Between CVC Activities

Step 4: Break the Weak Links

Step 5: Predict How Incumbents Will Respond

While competitors might respond in a thousand different ways, we can broadly classify these responses into two major categories: recoupling what the disruptor decoupled and preemptively decoupling, directly offering their customers the chance to decouple.

—

Decoupling unfolds in a patterned way across industries.

It occurs in situations where the incumbent company delivers two or more consumption activities to customers and then charges for the coupled activities.

Unlike with bundled products, coupled activities can always be broken apart into at least two, an activity that creates value (for instance, watching a TV show, talking to a friend on the phone, or browsing in-store for the right product) and an activity through which the company charges for value (for instance, getting viewers to watch ads, pay a subscription, connect to a mobile network, or buy a product on the shelf).

When a new entrant decouples the two activities and attempts to deliver a value-creating activity without a value-charging one, and when the decoupler monetizes this either by charging others (such as advertisers, retailers, or heavy users) or by simply charging less, established businesses face a serious threat.

—

responses to decoupling:

Most established businesses often attempt to respond in one of three ways:

They imitate the entrant

They buy it out

They attempt to suffocate it by drastically reducing prices

—

Say you run a company that sells cakes with frosting. A new startup allows your younger customers to acquire only the frosting, leaving you to deal with mountains of unpurchased frosting as you continue to bake and sell cakes. What can you do? One option is to force all cake buyers to purchase both cake and frosting together. The other alternative is to let customers buy only what they want. In other words, you can recouple the cake and the frosting back together, or you can preemptively decouple your cakes, allowing each part to be sold separately.

These two avenues are available to all incumbents, irrespective of industry.

—

Celiac Supplies, a specialty gluten-free grocery store based in Brisbane, Australia—decided to require every in-store customer either to make a purchase or to pay a $5 “just looking” fee for browsing.

—

Nestlé adopted a new model for its widely popular Nespresso business unit, selling high-end espresso coffeemakers at low prices and making most of their money on the coffee pods.

—

When advising established companies on rebalancing, I like to begin by first mapping out the entire CVC of my client’s customers in as much detail as possible. I specify all the activities I can discern that bear on how a customer actually learns of my client’s product or service, evaluates it, compares it with other products or services, chooses it, pays for it, uses it, reuses it, and disposes of it (if it is a physical product).

—

I think of the CVC as one big oil pipeline, with each segment of the pipeline a CVC activity. In a coupled process, all the segments are tightly welded together, and oil (i.e., value) flows continuously from the beginning of the pipeline to the end.

I then seek to understand how my clients can break up these segments of the pipeline and still ensure that value flows evenly and constantly from one end to the other.

That can only happen, of course, if there are no leaks at any point in the pipeline. If leakage does occur, then the company has created an opportunity for a competitor to come in, put a bucket under the leak, and capture much of the value without having to build the expensive drilling and pipeline infrastructure that my client has built. It behooves us to understand leakage in more detail. Formally, we can define it as follows:

—

If, say, customers receive $100 worth of value but pay only $79. The difference, $21, is what economists call “consumer surplus.” Conceptually, a person will buy a good or service only if the value to that person exceeds its price.

—

Is a startup poised to enter your market and attempt to decouple your business?

Executives should stay alert to the threat, continuously monitoring their risk of being decoupled. In particular, executives should constantly ask themselves three questions.

First: Does their company require customers to co-consume any of the company’s activities (e.g., browsing and buying)? In the unlikely case that the answer is no, the business need not worry, as there is nothing to decouple.

If the company does require co-consumption, then managers should pose a follow-up question:Can a disruptor conceivably separate the value-creating piece from another value-charging, value-eroding, or value-creating activity (for instance, using technology or business model innovation)? If not, managers should monitor for new innovations that could eventually make separation possible, but they need not worry about responding immediately. If the answer is yes, then new entrants might consider disrupting the incumbent by decoupling. In this scenario, managers should start taking that risk seriously and assess it objectively.

Taking the risk seriously leads managers to pose a third question: Does leakage exist that a disruptor might exploit in separating the co-consumed activities—as Amazon, for instance, did with traditional retailers? If not, managers should continue to monitor the situation but take no action. If leakage does exist, the incumbent should sound the alarm. The decoupling risk is real and a response via one of the two major avenues we described in the previous chapter is warranted.

3 questions for gauging the risk of being decoupled

—

The consideration set is one of the most important marketing concepts of the past few decades.

It posits that brands in consumer products don’t compete by vying at once for each customer in one big match-up. Rather, the competition resembles the Olympic Games, where swimmers, say, compete head-to-head for the gold medal in stages. There are preliminary races for each distance, and only eight or so swimmers make it through to compete in the finals. Swimmers competing in the finals are akin to a consideration set, and the number eight is the size of that set. When it comes to consumer purchases, each customer chooses his or her own set members and size.

How exactly do customers do that?

As academic research in marketing has shown, customers compose consideration sets on the basis of their awareness of and preferences for various options, as well as based on brand image, product differentiation, and category-specific factors.

Consideration sets can vary greatly by the person, category, and even country.

—

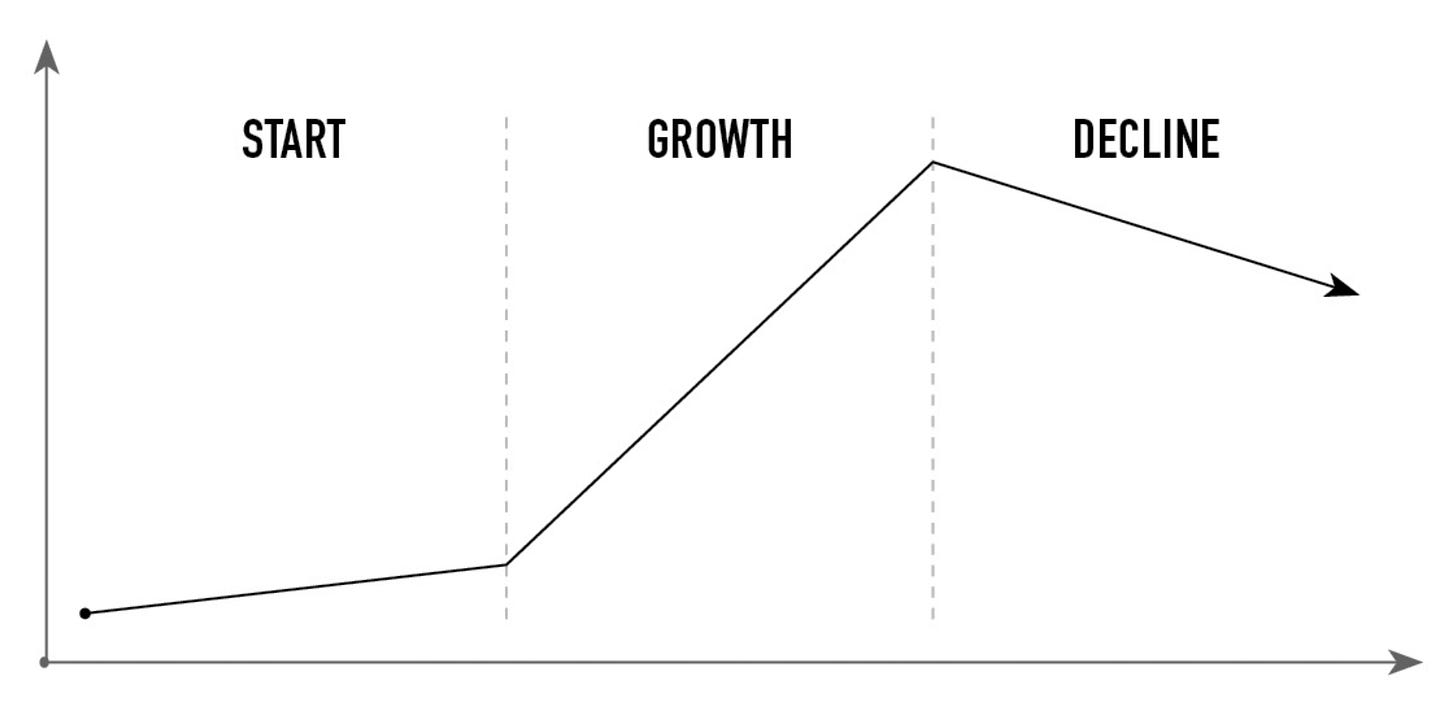

The lifecycle of a business

All businesses, large and small, traditional and disruptive, hew to a similar pattern in their journeys toward increased market penetration. During the initial phase, revenues and market share gains are typically slow. If companies survive this phase, they tend to progress into a second phase of much more rapid growth. Some companies flounder during this phase. Those that survive it eventually reach a third phase: a tapering off, slowing, or declining growth. The challenge here is to sustain growth as long as possible, or to jump-start new growth.

—

Businesses at the start phase all grapple with the challenge of acquiring their first customers in a cost-effective way, whereas businesses in the growth phase tend to focus more on deciding which new products to develop and markets to conquer, as well as how to organize people and processes to support these new initiatives. During the third phase, companies tend to focus more on how to counter a stall in growth and innovate themselves in or out of markets in which they have lost market share.

—

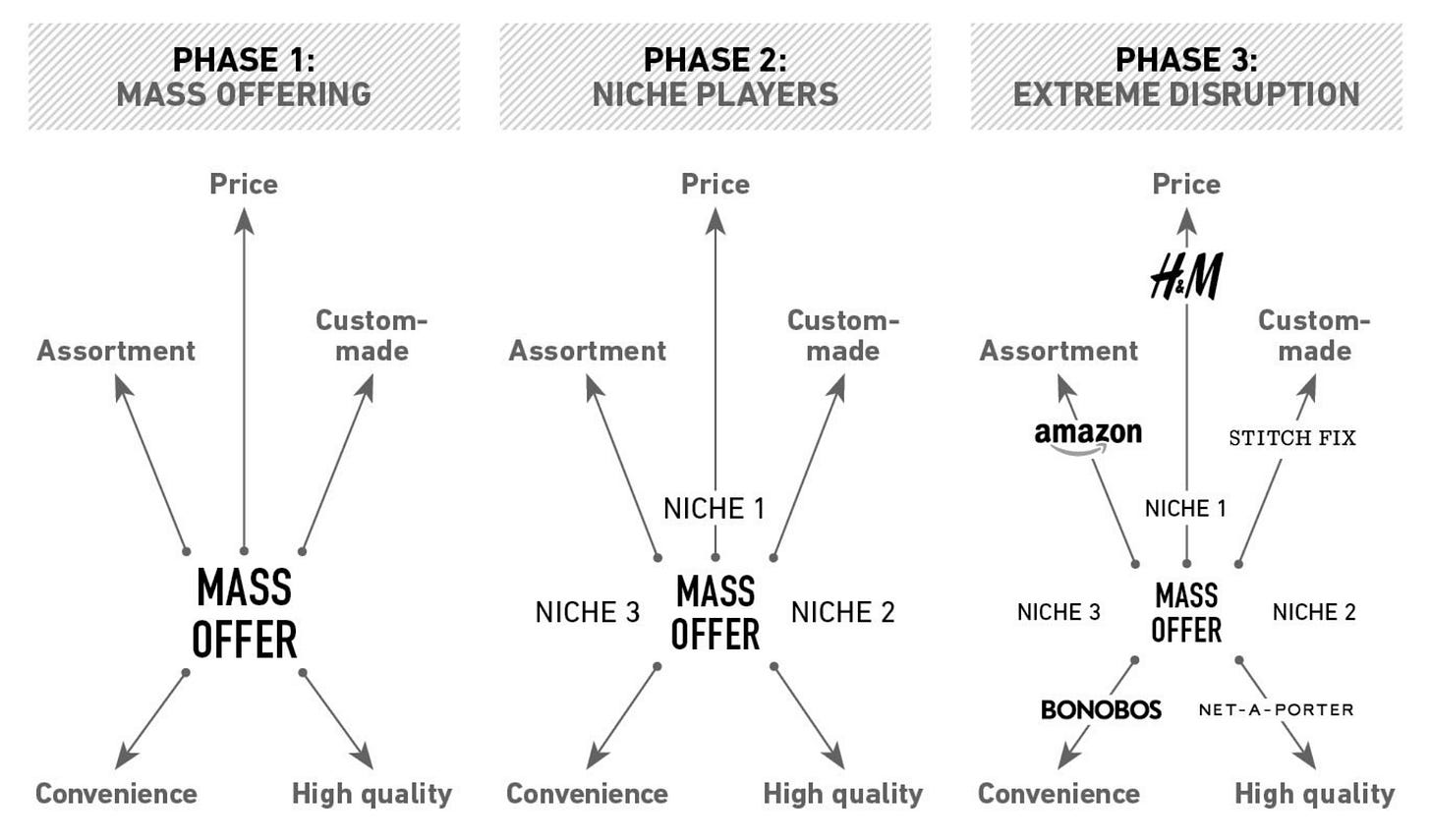

Evolution of the market landscape occupancy in clothing

Not

Note: the niche players attacking from the boundaries.

—

If you’re starting a disruptive business, especially one that seeks to decouple activities, you need to understand the history of specialization in the market. Who are the customers motivated to decouple? What are their dimensions of interest? How can you steal some of these customer activities for yourself? That must be your primary set of questions from the start.

—

Two-sided marketplaces are more challenging and complex to launch than other disruptors. It’s hard enough to acquire one type of customer in an online business. Two-sided marketplaces must acquire two distinct types of customers to their platforms, each with a distinct value proposition.

—

What can entrepreneurs learn about early customer acquisition from Airbnb and, by extension, from other fast-growing marketplaces such as Etsy and Uber?

Analyzing Airbnb’s story, we can discern the following seven principles at work:

“Buy” customers in bulk.

Acquiring users one by one takes too much time. A small startup needs to acquire customers in bulk, as Airbnb did during oversubscribed conferences and by tapping into Craigslist’s user base.

Don’t confront competitors directly.

A startup must avoid putting itself in the crosshairs of established incumbents. Don’t target their customers. Instead seek out customers they can’t or won’t serve. After concerts, more people need cabs than cab companies can handle.

Adopt non-scalable tactics.

Large tech companies tend to obsess over pursuing scalable tactics. If a tactic doesn’t work for thousands or millions of customers, these companies perceive it as a poor investment. Experts often recommend that startups behave similarly. Yet startups and large tech companies have different needs.

Incubate your early customers (and start with the suppliers).

Use low-tech, offline tools.

Tech startups tend to dismiss offline customer acquisition tools, such as organizing events, creating on-the-ground operations, or incentivizing users to talk to acquaintances about their services.

Favor operations over technology at first.

Technology can help business processes to scale, but it usually doesn’t allow them to get off the ground. For a disruptive business to succeed, it needs to work, plain and simple.

See your business through your customer’s eyes.

—

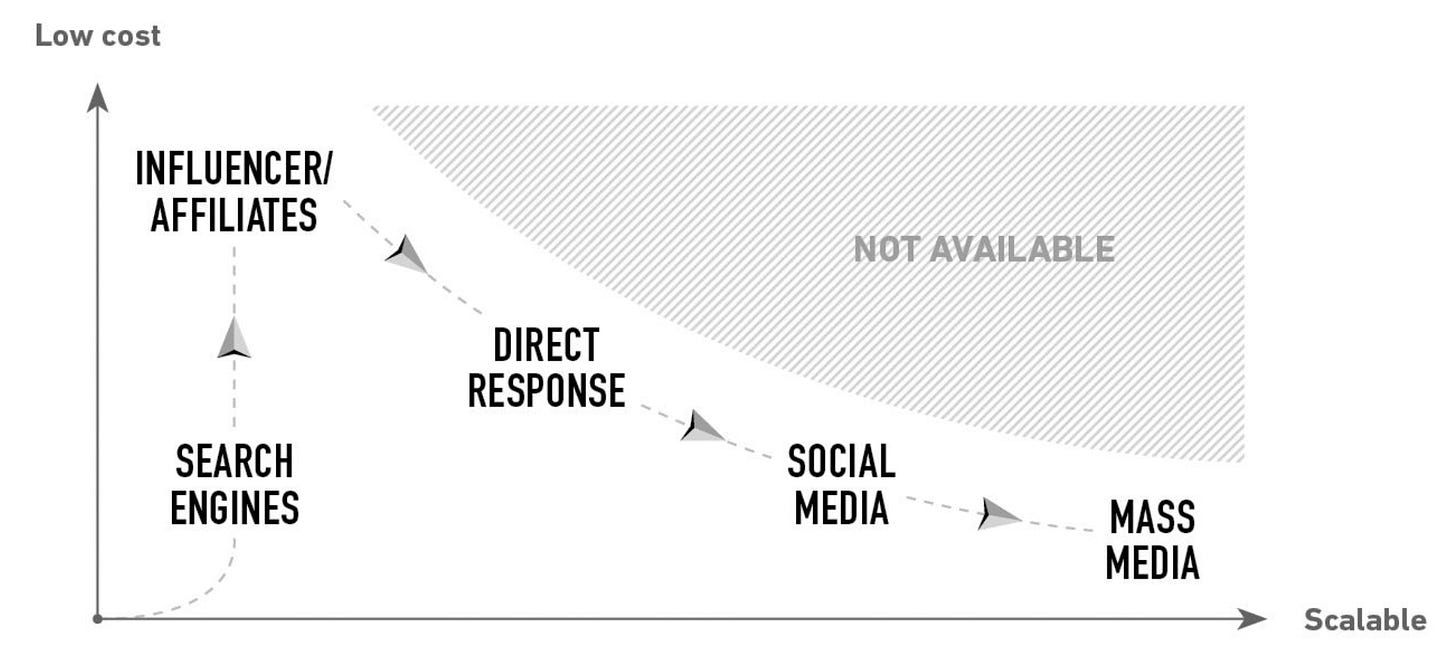

Customer acquisition channels for Rebag

—

Bain & Co. found that 80 percent of the time, a company’s higher rate of growth owed more to its performance relative to competitors than to the historical growth rate of the market it had chosen to enter.

—

As a brand manager, you may be surprised to learn that they regard your brand as significantly less versatile than you do. What you call closely adjacent, they may regard as far and remote.

—

For disruptors, revenue growth originates in one place, and one place only: customer acquisition.

—

Regardless of the means to get those resources, startups milk resources to get customers, instead of milking the customers.

—

Resource-centricity vs. Customer-cenricity

Resource-centricity: Certain firm-owned resources are your most valuable possessions. All your major business decisions should help you expand and leverage these resources.

Customer-centricity: Your customers are your most valuable possessions. All major business decisions should enhance your ability to increase the number of customers and leverage them.

—

Lack of innovation is a customer-centricity problem, not an R&D problem. Therefore, asking your product developers inside the company to “just innovate” will rarely head off a growth stall. To innovate, you first need to eliminate impediments to customer-centricity among both leaders and managers. This challenge brings you face-to-face with human nature. The reality is that companies are not customer-centric; people are.

—

Only two approaches exist for realigning employees’ priorities to customers’ needs.

First, they can change how employees earn financial recognition (salaries, bonuses) and promotions, providing other kinds of incentives as well. That’s a tall order in many large organizations, as quite often no single executive fully controls compensation and promotion decisions. It requires a collective effort at the leadership level.

Second, leaders can change the people, bringing in executives and managers who already are properly incentivized to put customers first. In sum, either change the incentives for the same people, or change the people.

—

Innovation means “novelty and significance.”

That is, new initiatives have to offer meaningful improvement for the customer—novelty alone isn’t enough.

—

In writing this book, one of my personal goals has been to demystify disruption by simplifying and clarifying the phenomenon. My other goal has been to redirect the attention of executives and managers, thus spurring them to take action.

—

We must learn to “cool ourselves down,” parting with the aggressive stance toward competition that many companies take. As the conventional thinking goes, business is war. Uber, Facebook, Google, and many more large companies around the world all have war rooms.* They aim to take territory. To fight back. To vanquish the competition. And to accomplish these goals, they mobilize various “strategic weapons” at their disposal.

—

The internet provides a cheap and accessible channel for distribution, marketing, and commerce, drastically lowering the cost of starting businesses. As a result, digital startups have flooded markets in consumer goods, electronics, transportation, industrials, and telecoms, to name a few. The large incumbents in these industries no longer face one or a few large “enemies,” but dozens or hundreds of small and unpredictable ones. The tasks of planning, strategizing, and executing no longer proceed in a top-down, hierarchical, deliberate, and predictable fashion. Rather, employees at all levels have to plan and execute continuously and iteratively to keep pace with the changes taking place around them.

Thanks so much for reading. Have a great week!

— Kevan

P.S. If you liked this email and have a quick moment, could you give hit the heart button below? It’d mean a ton to me and might help surface this newsletter for others. Thank you!